Did You Know? Breathing Training Can Provide Relief For Acid Reflux

According to the Canadian Digestive Health Foundation, one in six adult Canadians, or about 17%, are currently affected by gastrointestinal reflux disease (GERD). A systematic review completed in 2014 by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease in the United States, revealed that approximately 15 to 30% of Americans has GERD.

It is now recognized that conventional treatments for GERD such as the use of antacids are not effective (Vakil, 2006). The common prescription of a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) such as Zantac or using an over the counter remedy like Tums can actually increase the severity of acid reflux and lead to further damage to the lower esophagus (Fass R, 2005).

The rate of GERD will increase in the United States by 4% each year. This is attributed to the rising numbers of people being diagnosed with obesity, increased longevity, higher amounts of medications being taken for esophageal function related complaints, and Helicobacter pylori (H. Pylori) infection (Pandolfino JE, 2008).

GERD can usually be effectively treated without medication by learning to breathe properly, eating foods that maintain the ideal acidity levels in the stomach, and by avoiding foods and following lifestyle habits that could irritate the stomach (Casale M, 2016; Rohof WO, 2012; RT, 2006).

What is GERD?

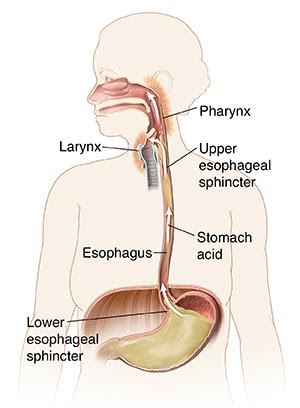

Heartburn, indigestion, or pyrosis, are terms used to describe the sensation of gaseousness, fullness, bloating, aching or burning in the chest or throat. GERD is diagnosed when people report two or more episodes each week of heartburn or its related symptoms (Vakil, 2006).

What are the symptoms of GERD?

Does someone you know have an oral, pharyngeal, laryngeal and pulmonary disorder? These conditions can be recognized in people who have an almost habitual clearing of the throat, coughing, a dry or sore throat, hoarseness, the feeling that something is stuck in their throat, and/or shortness of breath. These symptoms can occur with obesity because being overweight can increase the pressure on the contents of the stomach and cause the gastric contents to flow upwards.

Hydrochloric acid (HCl) from the stomach spilling upward into the throat region can cause irritation to the vocal cords (CDHF). The acid can cause one’s voice to change, cause the voice to become hoarse, lead to a sore throat, and/or a feeling that there is a lump in the throat. If stomach acid were to spill into the lungs, a cough, asthma, or infection can occur.

What is the conventional treatment?

Standard treatments for GERD include the recommendation of PPIs, hydrogen receptor blockers, or other over the counter antacids. Prescription medications are used next if these over the counter remedies are not helping to ease symptoms.

Using PPIs have not shown to be consistently effective (Fass R, 2005). Additionally, there are concerns about the side effects of the long-term use, particularly of PPIs (Rohoff et al., 2012). Frequent side effects of PPIs include: hip fractures, gastrinoma (a tumour in the pancreas or duodenum), diarrhea, community acquired pneumonia, and interactions with other drugs such as clopidogrel. In addition, the withdrawal of PPIs can lead to challenging symptoms (Jensen et al., 2006).

If over the counter and prescription medications are not effective, the next step in current conventional care is surgery. Typical procedures include laparoscopic fundoplication to wrap part of the upper stomach around the esophagus or a LINX reflux management system where a string of metallic beads are wrapped around the junction of the esophagus and the stomach (Thomas, 2018).

Conservative methods of treatment such as breathing training, lifestyle modifications, and holistic nutrition have been reported to be quite helpful when explored as an option prior to medication and/or surgery.

Why is training breathing helpful?

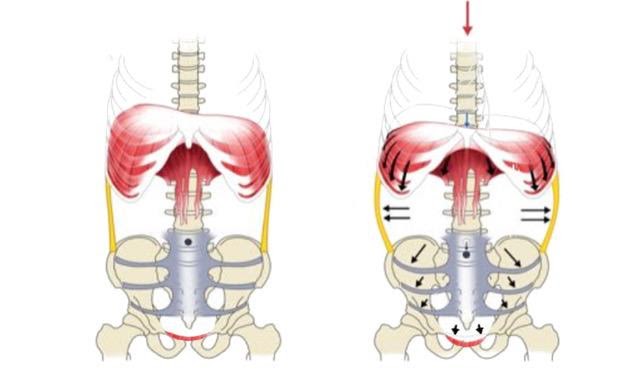

Despite little objective research available, breathing training may be an effective treatment for GERD with no side effects. When the striated muscle of the crural diaphragm contracts, it can actually create a physiological barrier at the gastroesophageal junction.

Training inspiration and thereby strengthening the diaphragm has been shown to increase the pressure to three times the current level of contraction in those affected by GERD. This strengthening of the diaphragm in effect creates an anti-reflux barrier (Miller, 2011).

In a study by Casale et al. (2016), four research papers were analyzed. There was a positive effect of breathing training noted in each experiment. The training implemented in each study was quite different, making broad recommendations for a particular kind of breathing training difficult. However, the positive findings in each study point to the effective use of breathing training for the prevention and treatment of GERD.

The researchers involved in this review called for a joint consensus examining the use of breathing training on the LES. This could be accomplished by randomized trials testing a variety of techniques to confirm an effective non-pharmacological treatment option for GERD.

What are the best next steps for treatment?

The review of the research connecting breathing, nutrition, and GERD clearly points to a future direction of effective conservative care. Breathing training for strengthening the diaphragm, eating specific foods and avoiding others, and adding particular and supplements can all help with the complete closure of the esophageal sphincter.

Breathing and holistic nutrition along with targeted supplementation are inexpensive approaches to treating GERD without the known side effects and risks of medication or surgery. With encouragement, doctors and their patients can be convinced to try lifestyle changes and specific breathing exercises as a first course of treatment. Ideally, early awareness of heartburn symptoms, simple breathing exercises, nutritional changes, and healthier lifestyle habits could lead to successful self-management.

Conservative treatment and public education about breathing training, lifestyle changes, and healthy nutrition could prevent heartburn and the diagnosis of GERD. These approaches to care could save the time and expense of physician and hospital visits, lower the rates of prescription medication use, and help avoid unnecessary surgery.

References

Canadian Digestive Health Foundation. (n.d.). Canadian Digestive Health Foundation Digestive Disorders. Retrieved 11 6, 2019, from Canadian Digestive Health Foundation: https://cdhf.ca/digestive-disorders/gerd/statistics/

Casale, M., Sabatino, L., Moffa, A., Capuano, F., Luccarelli, V., Vitali, M., ... & Salvinelli, F. (2016). Breathing training on lower esophageal sphincter as a complementary treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): a systematic review. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci, 20(21), 4547-4552.

Fass, R., Shapiro, M., Dekel, R., & Sewell, J. (2005). Systematic review: proton‐pump inhibitor failure in gastro‐oesophageal reflux disease–where next?. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics, 22(2), 79-94.

Hurtado, Dr. A., (2016). Nutrition Through The Lifespan, course notes, Institute For Holistic Nutrition, North York, Ontario, Canada.

Jensen, R. T. (2006). Consequences of long‐term proton pump blockade: insights from studies of patients with gastrinomas. Basic & clinical pharmacology & toxicology, 98(1), 4-19.

Kahrilas, P. J., Shaheen, N. J., & Vaezi, M. F. (2008). American Gastroenterological Association Institute technical review on the management of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology, 135(4), 1392-1413.

Miller, L. S., Vegesna, A. K., Brasseur, J. G., Braverman, A. S., & Ruggieri, M. R. (2011). The esophagogastric junction. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1232, 323.

Oleynikov, D. (2015). Surgical Approaches to Esophageal Disease, An Issue of Surgical Clinics, E-Book (Vol. 95, No. 3). Elsevier Health Sciences.

Pandolfino, J. E., Kwiatek, M. A., & Kahrilas, P. J. (2008). The pathophysiologic basis for epidemiologic trends in gastroesophageal reflux disease. Gastroenterology clinics of North America, 37(4), 827-843.

Rohof, W. O., Bennink, R. J., De Ruigh, A. A., Hirsch, D. P., Zwinderman, A. H., & Boeckxstaens, G. E. (2012). Effect of azithromycin on acid reflux, hiatus hernia and proximal acid pocket in the postprandial period. Gut, 61(12), 1670-1677.

Tauber, S., Gross, M., & Issing, W. J. (2002). Association of laryngopharyngeal symptoms with gastroesophageal reflux disease. The Laryngoscope, 112(5), 879-886.

Thomas, J. (2018, 10 8). GERD: Facts, Statistics, and You. Retrieved 11 6, 2019, from Healthline: https://www.healthline.com/health/gerd/facts-statistics-infographic#1

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease. Retrieved 11 6, 2019, from https://www.niddk.nih.gov/healthinformation/digestive-diseases/acid-reflux-ger-gerd-adults

Vakil, N. V. (2006). The Montreal Definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global evidence-based consensus. American Journal of Gastroenterology (101), 1900-19020.

Become a Guest Blogger!

We are now accepting applications for new Guest Bloggers! We encourage our fellow bloggers or aspiring bloggers to share their knowledge with the First Line Education community! If interested, please click the link below.